Special Sauce

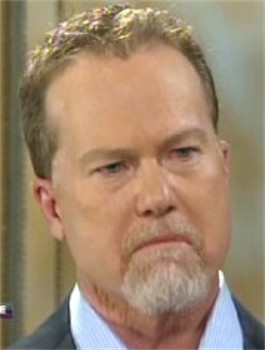

Mark McGwire: Hall of Famer or Hall of Shamer? Let’s discuss…

When I first got into baseball, the Oakland Athletics were my team. It’s hard to admit as a loyal baseball fan that I had a team before the Mariners, that my eternal and undying fanhood is not to my first love. It has become acceptable in our society not to marry your first love or have the same job for life, but sports fans are basically supposed to stick with one horse forever, for some reason especially in baseball. But alas, such is not my story.

I first discovered baseball watching softball games in public parks in Washington DC in the spring of 1988. I was intrigued by the strange shape of the field, the amalgam of so many people doing such specific things. More than anything, it looked like fun. It was nothing like the sports they had us play in PE, nothing like the endless running that people seemed to equate with organized sports. It had an artistry to it, a mystery, it demanded explanation. I wanted to know more and my parents – not exactly big baseball (or sports) people – couldn’t give me much beyond the very basics, which only deepened the mystery. They enjoyed the camaraderie of the public park games, too, though, and we were sometimes the only fans in the bleachers at these loosely organized games.

Then we moved to Oregon that summer and took a trip down to retrieve our stored items from the Central San Joaquin Valley in October. In a random hotel lobby, there was a TV displaying – wonder of wonders! – the same basic game I’d seen in the DC parks. But it was shinier, with classier uniforms, and thousands of fans. I parked in front of what turned out to be a World Series game, having no idea the significance or even that these were professionals. The desk clerk took me for an avid fan and bemusedly asked me which team I was rooting for. It hadn’t occurred to me. I looked back at the screen.

“The green team.”

Green, you see, was my favorite color. And so I was enthralled by the Oakland uniforms, triply thrilled when I realized the next spring that their mascot was an elephant. And their nickname was associated with the grade I diligently pursued in every subject. I fell hard for baseball. And not just baseball, but Major League Baseball. I learned most of the rules through third grade playground kickball, started reading boxscores in the daily paper (I remember vividly poring over the details of a matchup that appeared to be between the Boston Royals and the Kansas City Red Sox), tried out for Little League, infamously (in my own memory) thinking that the glove was supposed to go on the hand one found dominant, to the point of arguing with the person who gave me a glove out of the bucket of extras that my right-hand glove wouldn’t fit properly on my right hand. I overcame this, adored Little League, and started setting my sights on a Major League career.

And then came baseball cards, which were to dominate an incredible amount of my time and energy for the rest of my time in Oregon. And with baseball cards, a new awareness of the players. And quickly, before even the midpoint of the 1989 season, I had picked a clear favorite. He was a towering hulk of a player, but thoroughly competent and, moreover, seemed like an affable guy. He was the heart of the Oakland A’s lineup. His name? Mark McGwire.

Mark McGwire was my favorite baseball player for years, even after I had shifted gears from the A’s to the Mariners, the result of a long geologic wearing down from hearing over a hundred M’s games a year on the radio and falling for the excitement of the likes of Ken Griffey Jr. and Randy Johnson. Before the ’89 World Series, I had a lifesize Mark McGwire poster on the back of my door, which stayed there till we moved to New Mexico. I loved Big Mac, loved his effortless grace in smashing homers, his fearsome glower as he awaited the next hopeless pitch. He was perhaps an unlikely hero for a scrawny, terribly short right fielder (though I was quickly falling for Rickey Henderson too, with his wily speed, and I would soon become a catcher and really deepen my understanding of the game), but he just seemed to have the game figured out. He had the right attitude. And a cool name.

By 1998, I had grown to almost dislike the A’s after some intensely rivalrous years with the M’s in the new six-division structure of MLB and Big Mac had left them anyway. But I was over the moon about his season the summer before college, remember watching on a friend’s computer every at-bat after 60 homers. Wherever we were, whatever we were doing, someone would keep watch at the computer during Cardinals games and call us in and we’d all crowd around. Maybe it wasn’t every game, but that’s what it felt like at the time, and I’ll never forget 62, sending me over the moon with the high arc of the ball. There was the All-Star Game later, too, maybe the summer of ’99 or 2000 if I recall correctly, watching Big Mac rip what felt like 50 straight homers, all of them 450+ feet, just taking the cover off the ball and sending it as far as possible. I couldn’t stop smiling and my parents watched too and said that I knew all along, had picked the best guy so long ago.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock lately or hate baseball, you’re doubtless aware of Mark McGwire’s recent admission that he used steroids. The news is hardly earth-shattering for those paying attention to baseball in the last decade or so, watching people balloon into caricatures of themselves, popping out homers left and right amidst rumors of juiced balls and diluted pitching while baseball enjoyed the increased “game-saving” profits and turned a blind eye. The recrimination McGwire and his cohorts have faced has been severe and one might expect, given all my other proclivities, that I would feel betrayed by Big Mac, that he’d play Bill Richardson to my baseball fandom and I’d walk away thinking they were all crooks and cheats, unworthy of the homage we try to pay them.

But it’s not so. I diligently attended tens of San Francisco Giants games during Barry Bonds’ pursuit of the career home-run record, cheering every time he came to the plate. I still think fondly of McGwire, even as the media eviscerates him and the baseball writers laughably refuse to grant him passage to the Hall of Fame. I’m not wild about Rafael Palmeiro, but I think that’s just because he lied so vehemently about the whole thing. And I’ve always hated Roger Clemens and A-Rod since he ditched the Mariners for greed, so it’s really just an excuse to gang up on those guys.

Why? Is this just my loyalty to baseball overwhelming everything else I rationally feel? Everything I think about drugs and authenticity and everything else out the window? I mean, how inconsistent could I get, right?

The issue for me, and I haven’t seen this argument anywhere else (nor do I expect to), so I suspect I’m on my own here, is that the difference between steroids and everything else is basically nil. Yes, steroids are technically illegal, but so is refusing to sign up for the Selective Service. We live in a country where smoking marijuana is a vilified criminal activity while drinking alcohol is a lauded social rite. Law alone is no argument, no justification. Folks, the laws are stupid. And even if the laws about steroids are designed to protect people from long-term ill health, I know plenty of people who’ve been prescribed steroids for one thing or another. Heck, just a year ago, a Kaiser doc tried to put me on a lifetime steroid nasal spray to prevent all these ear infections.

Mark McGwire started talking early on about Andro, his legal daily supplement that he took to help build muscle. (I think it’s short for something, but I’m not sure what.) He recommended it to people publicly. And it was always the part of him that made me most uncomfortable, because something felt weird about taking a drug that would make you better at baseball in some way. And that, I think, is the point. All of it – lifting weights, even, let alone nutritional supplements or legal chemicals or other artificial inducements – is weird. Professional athletics have long relied more on science than on straight hard work. It’s about what to eat and what to drink and what to ingest and what to inject and what to build to specifically construct, through carefully researched science, the greatest athlete possible. It’s all artificial.

At that point, we have two choices. Either only let people play who walk in off the street and refuse to try to change their bodies… or let them do whatever they want. There are countless players who are on prescription ADD drugs that would otherwise be banned stimulants, but they get a special exemption. You probably can’t find a Major Leaguer (at least a position player) who isn’t on countless chemical supplements and substances. The science of sports is carefully managed and throws everything into doubt, especially when compared with the era of Babe Ruth, whose scientific regimen consisted of eating as much as possible. I mean, come on. Can you imagine Babe Ruth getting by in today’s game? They wouldn’t even give him a tryout till he shaped up.

I just don’t see the bright line between steroids and the rest of it. And while the law may have made things “unfair,” deterring a Ken Griffey Jr. or a Will Clark from trying steroids, baseball’s policy throughout the Steroids Era made it clear that they didn’t see the difference between steroids and other artificial substances either. You can call something illegal all you want, but if no one’s going to enforce the regulations and everyone heaps praise on what you’re doing, you pretty quickly realize that word doesn’t mean what you think it does.

As we get closer to a world of genetic engineering, this question isn’t going to go away. People will look first for the genes that impact growth and size and strength, beefing up their children in the hopes of lucrative contracts. And then where will we be? Do we bar these people and their unfair advantages, penalizing them for things they had literally no control over? Or do we start a space race for 11-foot tall mutants who hit every single ball over the wall till we have to rebuild the Polo Grounds to keep things in play? And what of our society’s increasing proliferation of BGH and other substances which have already increased our relative size and height?

Science will keep pushing the bar. And if one’s going to let some things in and not others, one’s being inconsistent. I don’t blame any of the people who took steroids in the so-called Steroids Era, though I still hate Clemens and A-Rod. I look down a bit more on those who lied, but I even understand their frustration with the double-standard retroactively being enforced on them. Big Mac, I forgive you. I get it. And I hope all the baseball writers get off their sanctimonious high horses long enough to let you into the Hall of Fame someday. After all, they didn’t exactly blow the cover off these stories in 1998 or 2000, however obvious they think your actions were then. They pocketed their money and made their reputations at those times, so who are they to deny you yours? Ex post facto standards are never fair and certainly not in America’s pastime.

And thanks for being honest about it, however long it took you to open up.

Cross-posted at StoreyTelling.

Storey — I know what it means to be a fan of a player who could hit the ball a mile. When I was a kid, if Mickey Mantle had a good day, I had a good day. You make some terrific arguments about the future of sport and what athletes may do one day to artificially improve their strength. However, the steroid, HGH era has destroyed something important to most baseball fans — baseball records. Baseball is the only sport where people really cared about records. Sixty homeruns in one season was a magic number. Then Roger Maris hit 61 and there was a new magician in town. Now that McGwire has hit 70, Bonds has hit 73 and Sosa has topped 60 twice (or was it 3 times) the record is now meaningless. Batting .400 is magical, but if steroids help a player get the bat around faster, then .400 is not what it once was. Until players are regularly tested for steroids and HGH, I believe no one should be admitted to the Hall of Fame. I still love baseball, but I will not respect the players or MLB until they agree to thorough testing, with players found cheating being banned from the sport. That goes for pitchers too.

Thanks for your thoughts, Rick – I could do a whole second post about this issue of records that you raise. In short, I couldn’t agree with you less.

Records are a great concept and they help foster baseball’s sense of history, which is one of the greatest that any sport has ever known. But records are only an approximation and have always been so. If you really believe that Babe Ruth could have hit 60 home runs against Randy Johnson and Nolan Ryan, then I tip my cap to you. But you’d be wrong. Bring Babe Ruth in his prime to hit against the pitchers of the ’90’s (you can hold back all the ‘roiders if you want) and he’d end up hitting .186 with 19 dingers.

You just can’t possibly compare the feats of the 1920’s with those of the 1950’s with those of the 1980’s. I mean, you can, and it makes for fun debate, but each accomplishment and performance belongs exclusively to the era in which it was created. What if they hadn’t lowered the mound? What if there were never a DH? What if there had never been expansion? Every one of these decisions massively alters the game to the point where the ripples override everything that happens. You can’t possibly balance and compensate enough to secure a vacuum of circumstances that protects the alleged sanctity of records.

I mean, do you really think Cal Ripken could’ve broken Lou Gherig’s games played streak without modern medicine and an army of trainers that haunt every MLB clubhouse in the modern era? That’s about the holiest of holies right there, and it relies just as much on modern technology and science as hitting home runs on steroids.

How about if baseball loses its popularity to the point where only the worst athletes compete? How bout the genetic manipulation I discussed? All of these have the same impact on the record books, they change the game fundamentally. Steroids were no different. Judge these players against the context and era of their time. McGwire, Sosa, Bonds, and even (gulp) Clemens are all no-brainer Hall of Famers. To say otherwise is to espouse, nay, mandate Harrison Bergeron levels of impossible manipulation.

Storey — generally speaking you can’t compare athletes from a past generation to modern athletes. Today’s athletes are bigger and stronger than in the past. However, this is less true of baseball players than it is of football and basketball players. Having seen Willie Mays, Ted Williams, Hank Aaron and Mickey Mantle, I know they would put up the same numbers today as they did 60 years ago. There were 16 teams in MLB then as opposed to 30 now. Baseball was the first choice of all great pro athletes. (Cal Ripkin’s record was not holy to me – he was a man who went to work every day sick or not. Like millions of people.) I never saw Babe Ruth play but when you consider he hit more homeruns than most teams, I consider him the greatest hitter of all time. I don’t know how he would do against modern pitching but I suspect that after a period of adjustment he would be a star. However, the central topic here is Mark McGwire and his use of steroids. His best years by far were when he was using steroids. Without them he would have a .250 lifetime batting average and he would need a ticket to get into the Hall of Fame. The Olympics bans steroids and HGH and therefore I believe the competition is relatively fair. (I know some countries have better training facilities than others.) You know what Bonds, McGwire and Sosa looked like before and after steroids — they changed into completely different people. Not because of tough training, but because of injections of serum. This cannot be acceptable